By US~Observer Staff

Lexington, Oklahoma – On July 16, 2008 the thick silence was punctuated only by the scraping of the metal chairs on the tile floor as Oklahoma inmate Reno Francis, his attorney Debra Hampton and his fiancé Verna Wood slid their chairs up to the table and prepared to face the parole board.

Introductions were made, the particulars of the 1970 crime were read, and the questioning began.

“Mr. Francis, did you commit this crime?” asked James Brown Sr., a member of the parole board.

“Yes, I did.”

“Can you tell us why you did that?”

“No, I can’t.”

“Well, can you explain what happened?”

Reno hesitated, “No, sir, I can’t.”

“I would like to hear what you have to say before I vote so I can make an informed decision. Why can’t you tell me what happened?”

Reno took a deep breath, shook his head, and responded, “Because I wasn’t there.”

“You weren’t there at the scene of the crime?”

“No sir, I wasn’t.”

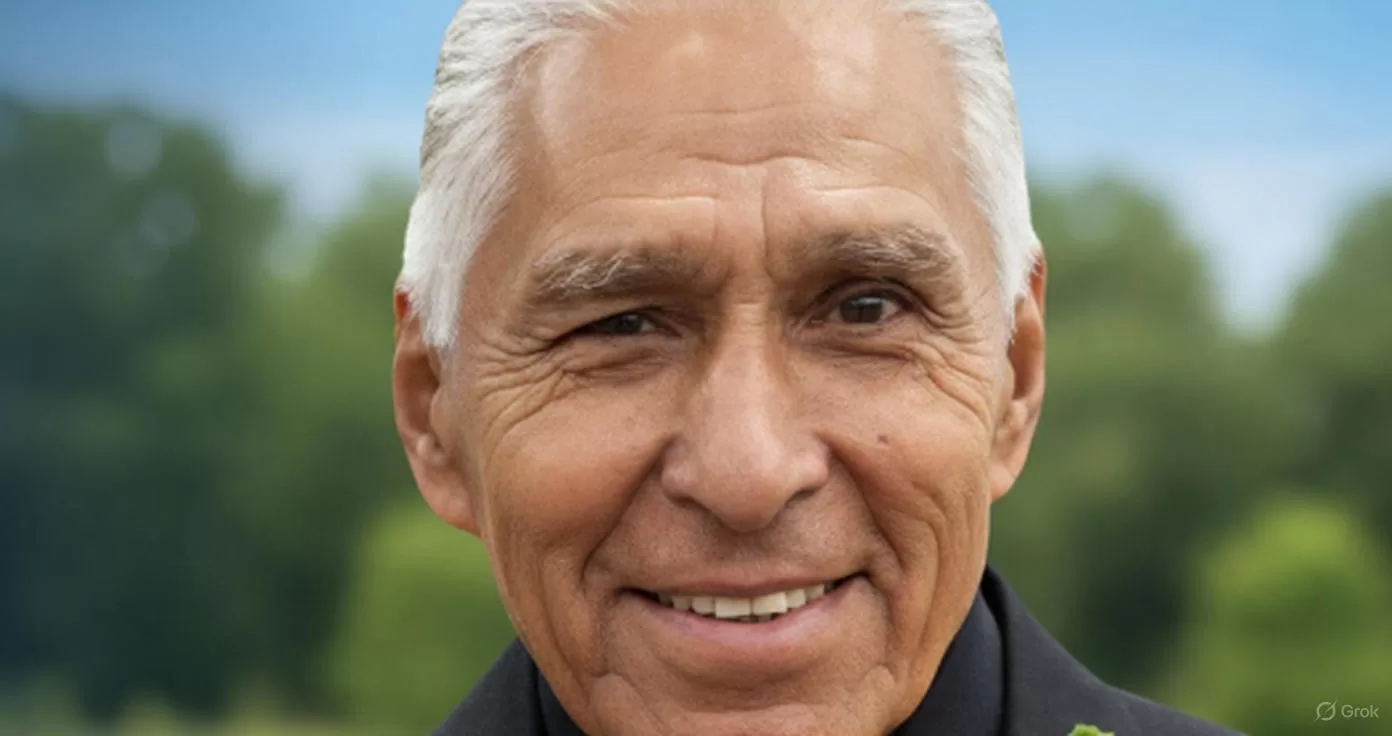

After encouragement from Mr. Brown, and parole board members Ms. Susan Loving and Ms. Lynnell Harkins, Reno explained about the events of the evening of August 1970. He had gone to a party in Holdenville, Oklahoma with a friend. After about an hour and a half Reno’s friend disappeared. Since Reno was not from Holdenville and didn’t know anyone else at the party he decided to leave. He was not familiar with the town and started walking, looking for a phone so that he could call someone to come get him and take him home. He walked until he came to a hospital where he went inside. As he was coming out, he noticed a police car in the parking lot. The officer in the car called to him, asking him to approach the police car. When Reno did so, the officer accused him of having been in a wreck involving several young Indians (Reno is Native American). Reno told the officer he did not know what he was talking about. The officer made Reno get into the car then took him to jail and charged him with being “high on an unknown substance.” Four days later Reno was told that there had been a murder at the party of a 13-year old girl and he was being charged with her murder.

The parole board questioned Reno as to why he confessed to the crime if he was not guilty. Reno, with help from his attorney, Ms. Hampton, explained that the assistant district attorney, John Turner, who prosecuted him, had threatened him with the death penalty if he did not confess. He told Reno he was going to die if he pled innocent but would only receive life in prison if he would plead guilty. Reno told the board that he did not write the confession and did not know who the person was who had written it.

Clearly uncomfortable with declaring his innocence before the parole board, Reno explained to them that he had always been told that an inmate should never claim to be innocent of the crime for which he is imprisoned when speaking to the parole board. He had been told that the board would not parole any person who did not take responsibility for their crime. At this the board indicated that they did not want anyone to claim guilt for something they did not do.

During the 2 minutes allowed Ms. Hampton to speak on Reno’s behalf she explained that she had gone to Holdenville and mapped out the location of the murder and also the path Reno had taken to the hospital that fateful night. When she had requested to see the evidence file in Reno’s case she had been told the file had been destroyed in a flood. She explained that Reno had used his time in prison in a good way by taking the programs offered to him and by becoming the spiritual leader in the Native American sweat lodge. She also stated that he had not received a “misconduct” in many years and that he has a family and home waiting for him upon his release.

The parole board members listened carefully and respectfully during the entire interview. They did not appear to rush or hurry Reno or his attorney in any way but seemed genuinely interested in hearing the truth. This reporter has sat through many parole hearings and would like to extend heartfelt appreciation to the board for the way they handled this case.

Attorney Hampton pointed out, it is somewhat difficult to understand how an innocent man could be sent to prison and still be there 38 years later! But as can be seen from the large number of innocent people who have been cleared and released in recent years, Reno is not alone. Sadly, the most common wrongful convictions involve murders and long sentences, possibly even death penalties for the convicted. Death row inmates represent a quarter of 1 percent of the prison population, however, 22 percent of those exonerated. In the event of such violent crimes prosecutors receive a great deal of pressure to “solve” the case. Therefore, many cases are resolved by placing innocent people in prison – thus quickly ending public scrutiny. All the while the guilty parties are free to kill again. There are even cases in which prosecutors have used the situation to further their own political ambitions. This has been done in cases where the prosecutor is fully aware that the guilt of the person they are sending to prison is questionable

In Reno’s case, assistant district attorney John Turner, who prosecuted him, is deceased. The head district attorney at the time of the murder, Mr. Gordon Melson, has written to the parole board three times asking them to grant Reno parole. How often does the prosecuting district attorney actually request release of an inmate? The U.S. Observer thanks Mr. Melson for his honesty and integrity and for his willingness to speak up for an innocent man.

Ms. Harkins, the president of the parole board asked if there were any more questions for Reno. When she received no response she informed him that he was dismissed to leave the room but his attorney and fiancée could stay behind to witness the vote of the board. Reno thanked the board and made his way to the door.

Besides the life sentence for murder Reno also has a 5 year sentence for “unauthorized use of a motor vehicle” and a 10 year sentence for “burning or destruction of a public building” (received when he was at Oklahoma State Penitentiary at McAlester while attempting to create a diversion by kicking a toilet off the wall to stop the beating of another inmate by prison guards). Both of these sentences are running consecutively to the life sentence meaning that if he is paroled off the life sentence he will only be paroled to the consecutive 5 year sentence (CS), not to the street. Many inmates have several sentences running concurrently, so that when the longest sentence has been served the others have been satisfied as well. Sadly that is not the case for Reno. Although he desperately wants to be home with his family, especially his children and grandchildren, he considers himself greatly blessed to have the possibility of having the life sentence off his shoulders.

After Reno left the room the board proceeded to vote on his parole from the life sentence to the “CS” sentence – the 5 year sentence. The vote began – “CS,” “CS,” “CS,” “CS,” “CS.” – It was unanimous! Every member of the board had voted for Reno to be paroled to the next sentence!

In any other state, except Oklahoma, Reno would now have been paroled. Oklahoma is the only state in the union in which the governor must approve all paroles. In the past several years thousands of paroles have been denied by the governor, which have been recommended by the parole board. This serves to keep many deserving inmates behind bars and digs deeply into the pockets of Oklahoma taxpayers. At an approximate annual cost of $17,688 per inmate, the cost of keeping those denied by the governor in prison is in the millions.

Reno Francis, an innocent man, has already spent 38 years of his life in prison for a crime he did not commit (read “From Arrest to Prison in 17 Days” on our website – usobserver.com). The U.S. Observer calls for the Oklahoma State Governor Brad Henry to approve Reno’s parole. We strongly encourage him to not only parole Reno to the next sentence whereby he must still spend more years in prison but to commute Reno’s sentence to “time served” and let him go home! What more does the State of Oklahoma want from an innocent man? Surely 38 years is more than enough for Reno to serve – especially when the person who committed this crime is still out there somewhere enjoying life as a free man.

After the hearing Reno made the statement that he felt as if a huge weight had been lifted off him. For the first time in 38 years he had been allowed by someone in authority to tell his story. He had been treated with respect and allowed to speak the truth. This newspaper commends the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board for their respectful treatment of Mr. Francis and for permitting him to tell the truth. After all, is that not what our justice system is supposed to be about – discovering truth? It was not designed to be governed by politics or to further careers, but to protect the falsely accused while also protecting the public.

Truth and justice? The Oklahoma parole board obviously values these precepts. We pray they are equally important to Governor Brad Henry.

Editor’s Note: There are many men and women who are factually innocent and sitting behind bars.

To read more about Reno Francis and his quest for freedom, log onto usobserver.com. Reno’s story can be found in the following issues: 2007-Edition 15, Edition 18, Edition 19.